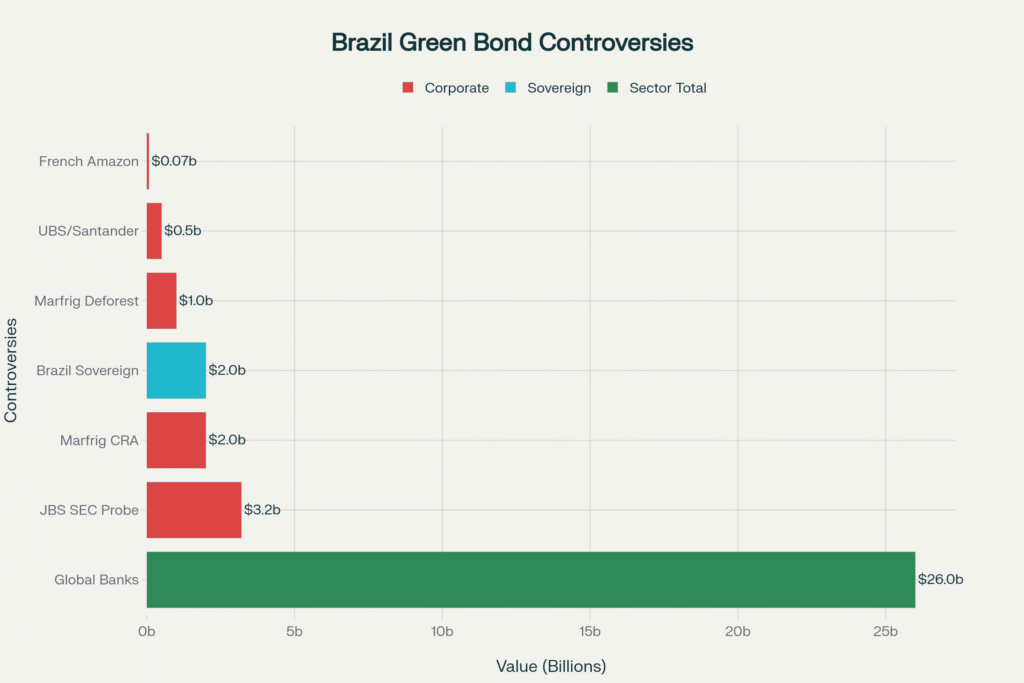

The sustainable finance sector is reeling from revelations of a sprawling network of Brazilian green bond scandals that have exposed fundamental weaknesses in ESG oversight and due diligence across global capital markets. At the center of this crisis lies over $5 billion in purportedly “green” financing that has been directly or indirectly linked to Amazon rainforest destruction, illegal deforestation, and systematic greenwashing. The scandals encompass everything from JBS’s $3.2 billion sustainability-linked bond fraud currently under SEC investigation to Marfrig’s recent exposure for using $1 billion in bond proceeds to purchase cattle from illegally deforested areas.

This comprehensive investigation reveals how European banks including UBS, Santander, BNP Paribas, and others facilitated hundreds of millions in “green” bond issuances that ultimately funded environmental destruction, while Brazilian corporations exploited weak regulatory frameworks to access international capital markets under false sustainability pretenses. The scale of the deception extends beyond individual corporate malfeasance to encompass systemic failures in green bond verification, supply chain monitoring, and regulatory oversight that have allowed sustainability fraud to flourish across one of the world’s most critical ecosystems.

The JBS Sustainability-Linked Bond Fraud: A $3.2 Billion Case Study in Greenwashing

SEC Investigation Exposes Systematic Deception

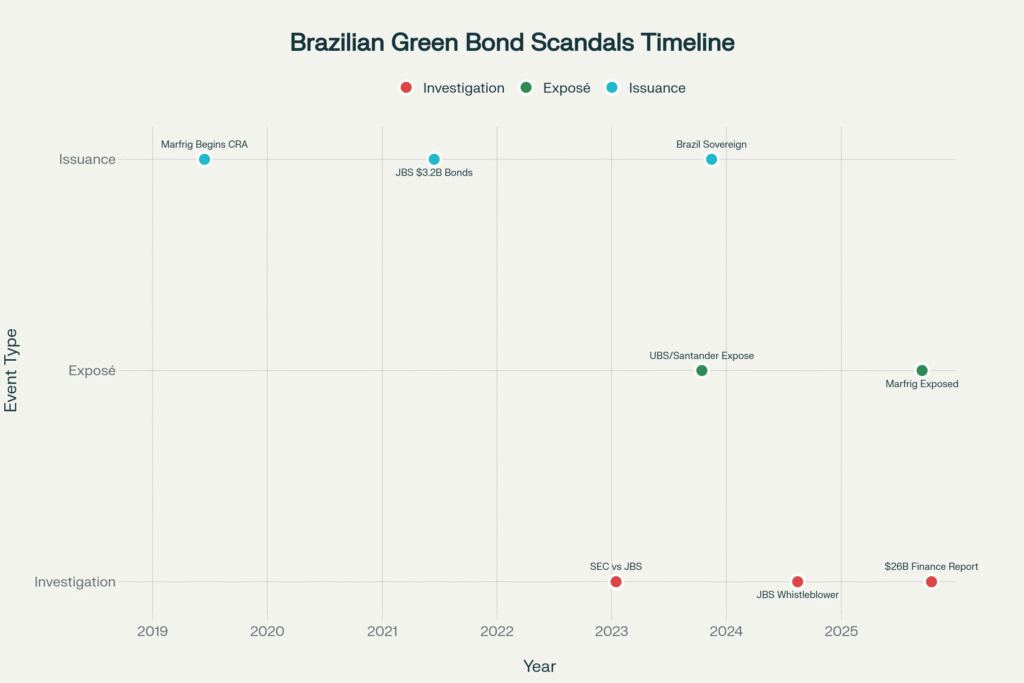

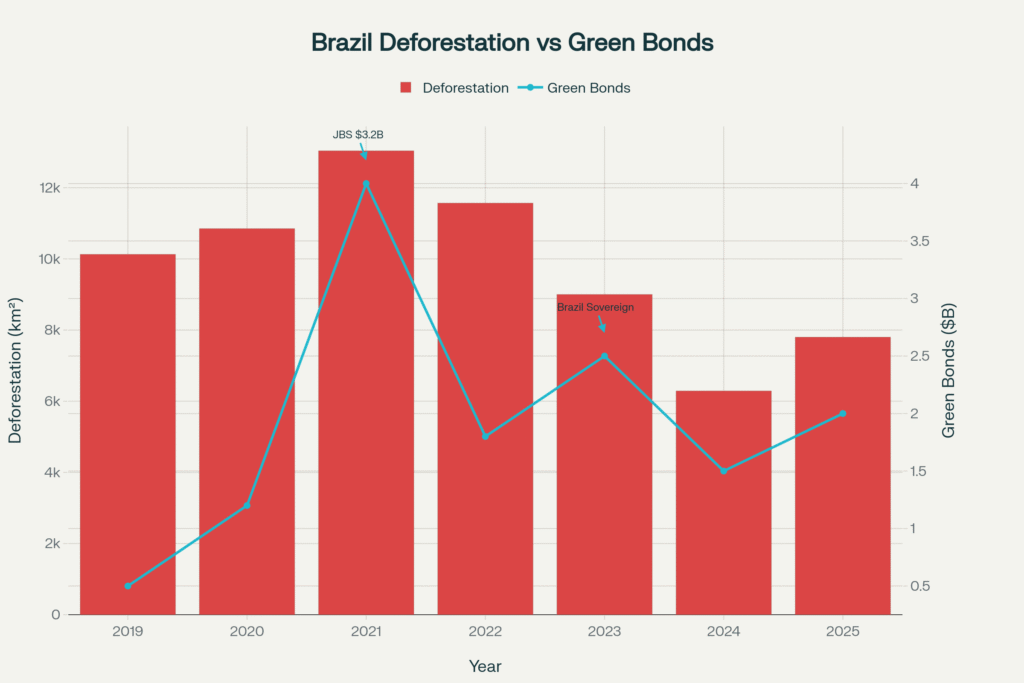

The JBS scandal represents perhaps the most egregious example of green bond fraud in the sustainable finance sector’s history, with environmental advocacy group Mighty Earth filing the first-ever SEC whistleblower complaint against sustainability-linked bonds in January 2023. The complaint details how JBS, the world’s largest meat processor, raised $3.2 billion through four separate bond issuances in 2021 by making misleading claims about achieving net-zero emissions by 2040 while systematically excluding the 97% of emissions that come from their supply chain (Scope 3 emissions).

The fundamental deception lay in JBS’s emission accounting methodology, which conveniently omitted the vast majority of the company’s climate impact—including methane emissions from cattle and deforestation caused by feed production and grazing land expansion. According to Mighty Earth’s analysis, JBS’s actual emissions have increased in recent years rather than decreased, making their net-zero commitments not just aspirational but demonstrably false. The company also failed to disclose the actual number of animals they slaughter annually, denying investors critical information needed to assess the credibility of their climate commitments.

The SEC’s newly created Climate and ESG Task Force is now investigating the bonds, with the case potentially setting precedent for how regulators will handle greenwashing in sustainable finance markets. Glenn Hurowitz, CEO of Mighty Earth, characterized the case bluntly: “The fact that the meat company arguably responsible for more climate pollution and deforestation than any other in the world was able to raise $3.2 billion through green bonds is an indictment of the utter lack of safeguards in the world of ESG investing”. The investigation has gained additional urgency as JBS seeks to list on the New York Stock Exchange, with critics dubbing it potentially “the biggest climate risk IPO in history”.

Supply Chain Deforestation and Corporate Governance Failures

Beyond emissions fraud, JBS faces mounting evidence of continued links to Amazon deforestation despite pledges to eliminate illegal deforestation from its supply chains. Global Witness investigations have linked JBS to more than 80,000 football fields of deforestation in Brazil, while the company maintains insufficient monitoring systems to prevent cattle from illegally deforested areas entering their supply chains. The New York Attorney General Letitia James has filed a lawsuit against JBS, accusing the company of having “no viable plan” to meet its net-zero commitments.

The governance issues extend beyond environmental concerns to encompass a history of corruption and financial misconduct. JBS executives were involved in a widespread corruption scandal in Brazil in 2017 and pleaded guilty to U.S. foreign bribery charges in 2020. These governance failures raise fundamental questions about whether institutional investors properly assessed the risk of investing in sustainability-linked bonds issued by a company with such a problematic track record.

The bond structure itself reveals sophisticated financial engineering designed to minimize accountability while maximizing access to sustainability-focused capital. The bonds include provisions for “step-up” interest rates if JBS fails to meet its emissions targets, but critics argue these penalties are insufficient to compensate for the environmental damage caused by the company’s operations. More fundamentally, the emissions targets themselves exclude the vast majority of JBS’s climate impact, making the entire sustainability-linked structure meaningless from an environmental perspective.

The Marfrig Deforestation Money Trail: $1 Billion in Illegal Cattle Purchases

Mongabay Investigation Exposes Board Chairman Conflicts

A September 2025 investigation by Mongabay and the Center for Climate Crime Analysis revealed that Marfrig Global Foods spent $1 billion from bonds to purchase cattle from ranches linked to its board chairman, with portions of that cattle originating from illegally deforested areas of the Amazon and Cerrado. The investigation exposed a sophisticated money-laundering scheme where half of Marfrig’s 11 billion reais ($2 billion) in Agribusiness Receivables Certificates (CRA) since 2019 was used exclusively to purchase cattle from feedlots run by MFG Agropecuária, whose managing partner is Marfrig’s board chairman, Marcos Antonio Molina dos Santos.

The investigation revealed specific cases of cattle originating from illegally deforested properties, including the Dom Ângelo ranch owned by Cassio Gradela, which was embargoed by Brazilian environmental agency IBAMA for illegal deforestation. Despite the embargo, cattle from this property and other problematic ranches entered Marfrig’s supply chain through a complex network of intermediary feedlots designed to obscure the origin of illegally-sourced cattle. The deforestation on these properties occurred as close as 9 kilometers from Indigenous territories, highlighting the human rights implications of the company’s operations.

Marfrig’s monitoring systems, which the company claims track nearly 90% of indirect suppliers in the Amazon, contain significant blind spots that enable ranchers to circumvent sustainability controls through fraudulent documentation. The investigation found evidence of cattle transfers between properties owned by the same individuals but registered under different names, creating paper trails that appear compliant while enabling continued sourcing from illegal deforestation areas. This systematic circumvention of sustainability controls reveals fundamental flaws in current supply chain monitoring approaches relied upon by green bond investors.

CRA Bond Structure Facilitates Environmental Crime

The Agribusiness Receivables Certificates (CRA) bond structure that Marfrig exploited represents a significant regulatory loophole in sustainable finance oversight. These bonds, specifically linked to Brazilian agribusiness, are little-known outside the country and are not tracked in detail by major financial data platforms like Bloomberg or Refinitiv. The CRA market has expanded by over 500% in five years, growing from R$7 billion ($1.15 billion) in 2018 to almost R$43 billion ($7.1 billion) in 2022, creating a massive pool of capital with limited transparency or environmental oversight.

European banks including UBS and Santander have served as intermediaries for hundreds of millions in CRA issuances that ultimately funded environmental destruction. A joint investigation by Greenpeace’s Unearthed and O Joio e O Trigo found that these “green” bonds financed farmers and ranchers accused of environmental and human rights abuses, including individuals accused of holding workers in “slave-like” conditions and companies identified as major deforesters. The banks earned fees of 3-5% of total offerings while conducting minimal due diligence on the ultimate use of proceeds.

The geographic concentration of CRA-funded expansion in the Matopiba region (covering parts of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí, and Bahia states) has driven accelerated deforestation in the Cerrado savanna. This region, being rapidly transformed into Brazil’s newest agribusiness frontier, accounted for 61% of all Cerrado deforestation from August 2020 to July 2021. The weak legal protections in the Cerrado—where farmers can deforest up to 80% of their property in some areas—combined with foreign capital inflows through CRA bonds, has intensified land grabbing and environmental destruction.

Sovereign Sustainability Bonds: Brazil’s $2 Billion Credibility Gap

Government Green Bonds Amid Continued Deforestation

Brazil’s launch of its first sovereign sustainable bonds in November 2023, raising $2 billion for environmental and social projects, occurred against a backdrop of continued Amazon deforestation that raises questions about the credibility of government climate commitments. While the Lula administration has significantly reduced deforestation rates compared to the Bolsonaro era, Amazon clearing still reached approximately 7,800 km² in 2025, indicating that substantial forest loss continues even as the government markets itself as a leader in environmental protection.

The bond structure attempts to address credibility concerns by allocating proceeds equally between environmental and social initiatives, with the government committing to regular reporting on use of proceeds and environmental outcomes. However, critics argue that the bonds essentially allow the government to fund general environmental programs while failing to address the structural economic incentives that drive deforestation. Deputy Treasury Secretary Otavio Ladeira explicitly rejected proposals for dedicated Amazon bonds, stating that “regular and predictable funding is preferable to creating separate instruments like Amazon bonds”.

The timing of the sovereign bond issuance, coming amid global scrutiny of Brazil’s environmental policies and corporate sustainability scandals, appears calculated to restore international confidence in Brazil’s climate commitments. However, the government’s refusal to create dedicated Amazon protection bonds, despite banking industry estimates that such instruments could raise $10 billion at exceptionally low costs, suggests a reluctance to accept binding environmental performance metrics that could result in financial penalties. This approach maintains maximum government flexibility while potentially undermining the environmental integrity that sustainable bond investors expect.

Integration with Corporate Sustainability Failures

The credibility gap between Brazil’s sovereign sustainable bonds and the country’s corporate sustainability scandals creates a fundamental contradiction in the country’s approach to sustainable finance. While the government markets Brazil as a leader in environmental protection and sustainable development, major Brazilian corporations continue accessing international capital markets through fraudulent green bonds that fund environmental destruction. This dual-track approach—government sustainability marketing combined with corporate environmental crime—undermines the integrity of Brazil’s entire sustainable finance ecosystem.

International investors face the challenge of reconciling Brazil’s official climate commitments with the reality of continued corporate-driven deforestation. The government’s environmental policies, while improved under President Lula, have not prevented systematic abuse of green bond markets by Brazilian agribusiness companies. This regulatory failure raises questions about whether sovereign sustainability bonds can deliver meaningful environmental outcomes when the same government fails to prevent corporate greenwashing in domestic capital markets.

The interconnection between sovereign and corporate sustainability failures is evident in the government’s continued support for agribusiness expansion in environmentally sensitive areas. Despite pledges to achieve zero deforestation by 2030, the government continues to permit legal deforestation in the Cerrado and has failed to strengthen enforcement against illegal clearing in the Amazon. This policy contradiction enables continued corporate abuse of green bond markets while providing political cover through sovereign sustainability bond issuances that appear to demonstrate environmental commitment.

European Bank Complicity and Regulatory Failures

Major Financial Institutions Enable Environmental Crime

European banks have played a central role in facilitating Brazilian green bond fraud, earning hundreds of millions in fees while conducting minimal due diligence on environmental claims. UBS and Santander, among the world’s largest investment banks, coordinated “green” CRA issuances worth hundreds of millions that funded farmers and ranchers accused of deforestation, land grabbing, and human rights abuses. The banks’ fee structures—typically 3-5% of total issuances—create strong incentives to complete transactions regardless of environmental integrity.

The systematic nature of European bank involvement suggests institutional failures rather than isolated incidents. Between 2013 and 2021, four French banks (BNP Paribas, Crédit Agricole, BPCE, and AXA) invested nearly $70 million in bonds issued by Brazilian meat companies, generating $11.7 million in profits. A coalition of NGOs filed criminal complaints against these banks for money laundering and concealment related to financing companies driving deforestation. This represents the first time French banks have faced criminal charges for money laundering related to environmental crimes.

The regulatory response has been inadequate given the scale of the problem. While some European banks have faced fines for greenwashing—such as Deutsche Bank’s asset management arm DWS receiving a €25 million penalty—these sanctions are minimal compared to the profits generated from facilitating environmental destruction. The UK’s Competition and Markets Authority announced plans for large-scale enforcement of its Green Claims Code starting in autumn 2025, but this reactive approach comes years after systematic abuse of green bond markets has already occurred.

Systemic Due Diligence Failures

The European bank involvement in Brazilian green bond scandals reveals fundamental weaknesses in ESG due diligence processes across the financial sector. Despite having access to sophisticated environmental monitoring tools and extensive research capabilities, major banks repeatedly failed to identify obvious red flags in companies with well-documented histories of environmental destruction and corporate governance failures. This suggests that current ESG integration processes prioritize marketing and fee generation over genuine environmental risk assessment.

The failure of ESG rating agencies and sustainability consultants to flag obvious problems with Brazilian green bonds indicates broader system integrity issues. Companies like JBS, with documented histories of deforestation, corruption, and human rights abuses, received investment-grade sustainability ratings that enabled access to green bond markets. The disconnect between sustainability ratings and environmental reality suggests that current ESG evaluation methodologies are fundamentally inadequate for identifying greenwashing.

Legal liability for European banks may extend beyond regulatory fines to encompass investor lawsuits and reputational damage that could fundamentally alter the sustainable finance landscape. As the scale of Brazilian green bond fraud becomes apparent, institutional investors who purchased these instruments may seek compensation from the banks that facilitated their issuance. The potential for massive legal liability could force European banks to fundamentally restructure their approach to sustainable finance due diligence and risk management.

Regulatory Response and Market Implications

SEC Investigation Sets Global Precedent

The SEC’s investigation of JBS’s sustainability-linked bonds represents a watershed moment for sustainable finance regulation, potentially establishing precedents that could reshape green bond markets globally. The investigation, conducted by the SEC’s Climate and ESG Task Force, focuses on whether JBS misled investors about its environmental commitments and emissions reduction capabilities. If the SEC takes enforcement action, it could establish clear legal standards for sustainability bond disclosures and create significant liability for both issuers and underwriters.

The investigation’s scope extends beyond JBS to encompass the broader sustainability-linked bond market structure and oversight mechanisms. SEC scrutiny of emission accounting methodologies, supply chain monitoring systems, and corporate governance practices could establish minimum standards that fundamentally alter how companies access sustainable finance markets. The precedent could be particularly significant for emerging market issuers, who have historically faced less stringent disclosure requirements than developed market companies.

International regulatory coordination may emerge from the Brazilian green bond scandals, with European and other regulators potentially following the SEC’s lead in investigating sustainability bond fraud. The French criminal complaint against banks financing deforestation and the UK’s enhanced green claims enforcement suggest a broader regulatory crackdown on sustainability-related financial crime. This coordinated approach could create global standards for green bond verification and due diligence that prevent future scandals.

Market Structure Reforms and Investor Protection

The Brazilian green bond scandals are likely to accelerate regulatory reforms aimed at strengthening investor protection and market integrity in sustainable finance markets. Proposed reforms include mandatory third-party verification of sustainability claims, standardized emission accounting methodologies, and enhanced supply chain monitoring requirements. The European Union’s upcoming Green Bond Standard, which requires strict verification and reporting, represents the type of regulatory response that could prevent future greenwashing scandals.

Investor lawsuits related to Brazilian green bond fraud could establish legal precedents that fundamentally alter liability structures in sustainable finance markets. Institutional investors who purchased bonds based on fraudulent sustainability claims may seek compensation not only from issuers but also from underwriters, rating agencies, and sustainability consultants who facilitated the transactions. These legal actions could create liability standards that force all market participants to substantially strengthen their due diligence processes.

The reputational damage to Brazilian sustainable finance markets may create lasting impacts on the country’s access to international capital markets. International investors increasingly view Brazilian sustainability claims with skepticism, potentially increasing borrowing costs for legitimate sustainable projects and companies. This reputational spillover effect could incentivize stronger government enforcement of environmental regulations and corporate sustainability standards.

Supply Chain Finance and Agricultural Commodity Markets

CRA Bond Structure Facilitates Systematic Fraud

The Agribusiness Receivables Certificates (CRA) that enabled much of the Brazilian green bond fraud represent a broader problem with agricultural commodity financing that extends far beyond individual corporate malfeasance. The CRA structure allows agricultural companies to securitize future commodity sales, creating bonds backed by agricultural products that may not yet exist or may be sourced from unknown suppliers. This forward-looking structure makes it virtually impossible for bond investors to verify the environmental integrity of the underlying agricultural production.

The rapid growth of the CRA market—expanding over 500% in five years—has occurred without corresponding development of environmental oversight or sustainability verification mechanisms. The bonds are often marketed as “green” based on general sustainability commitments rather than specific environmental performance criteria, creating opportunities for systematic greenwashing. The concentration of CRA expansion in the environmentally sensitive Matopiba region has directly contributed to accelerated deforestation and biodiversity loss.

International banks’ involvement in CRA markets creates global financial exposure to Brazilian environmental crime, with European, American, and Asian institutions indirectly financing deforestation through seemingly legitimate financial instruments. The bonds’ complex structure makes it difficult for investors to trace the ultimate use of proceeds, enabling agricultural companies to access international capital markets while maintaining destructive environmental practices. This structural opacity represents a fundamental flaw in current sustainable finance architecture.

Commodity Trading and Supply Chain Opacity

The role of major commodity trading companies in facilitating green bond fraud highlights broader problems with agricultural supply chain transparency and accountability. Companies like Cargill, which purchases from agricultural producers funded by fraudulent green bonds, maintain that they have adequate supply chain monitoring systems while continuing to source from suppliers with documented deforestation links. This willful blindness enables continued environmental destruction while providing plausible deniability for international commodity buyers.

The geographic concentration of problematic CRA funding in frontier agricultural regions creates systematic environmental risks that extend beyond individual company operations. The Matopiba region’s rapid agricultural expansion, funded partly by fraudulent green bonds, is driving landscape-level environmental changes including deforestation, water system disruption, and indigenous community displacement. These regional impacts create environmental liabilities that could affect all agricultural producers and commodity buyers operating in the area.

Supply chain finance mechanisms like CRAs create perverse incentives that reward environmental destruction while penalizing sustainable practices. Agricultural producers can access lower-cost capital by participating in fraudulent green bond programs rather than investing in genuine sustainability improvements. This inverted incentive structure undermines legitimate sustainable agriculture initiatives while channeling capital toward environmentally destructive practices.

Environmental Justice and Indigenous Rights Implications

Indigenous Territory Impacts and Human Rights Violations

The Brazilian green bond scandals have had devastating impacts on Indigenous communities, with cattle operations funded by fraudulent sustainability bonds operating as close as 9 kilometers from Indigenous territories. The systematic destruction of forests adjacent to Indigenous lands threatens traditional livelihoods, disrupts water systems, and enables further encroachment on protected areas. Indigenous rights organizations have documented numerous cases of land grabbing and environmental destruction directly linked to agricultural operations funded by green bonds.

The human rights implications extend beyond environmental impacts to encompass labor abuses and community displacement. Investigations have linked green bond-funded operations to ranchers accused of maintaining workers in “slave-like” conditions and agricultural companies that have displaced traditional communities from their ancestral lands. The use of “green” financing to fund human rights abuses represents a fundamental perversion of sustainable finance principles.

The lack of Indigenous community consultation in green bond verification processes violates international standards for sustainable finance and Indigenous rights. Current green bond frameworks focus on environmental metrics while ignoring the social impacts on Indigenous and traditional communities affected by funded projects. This oversight enables continued environmental and cultural destruction under the guise of sustainable development.

Regional Environmental Degradation and Biodiversity Loss

The Cerrado savanna, targeted by many CRA-funded agricultural expansion projects, represents one of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems and a critical carbon sink for global climate stability. The biome concentrates 5% of global plant and animal biodiversity while playing a fundamental role in South America’s water supply and climate regulation. The systematic destruction of this ecosystem, funded partly by fraudulent green bonds, represents an irreversible loss of global environmental assets.

Water system disruption from CRA-funded deforestation affects communities far beyond the immediate project areas. The Cerrado serves as the “water tower” of South America, feeding major river systems including the Amazon, São Francisco, and Paraná rivers. Deforestation in the headwaters regions, enabled by green bond financing, threatens water security for hundreds of millions of people across the continent.

The concentration of environmental destruction in specific regions creates cumulative impacts that exceed the sum of individual project effects. The Matopiba region’s rapid transformation from natural savanna to industrial agriculture has created landscape-level environmental changes including altered precipitation patterns, increased fire risk, and ecosystem fragmentation. These regional impacts represent systemic environmental damage that cannot be addressed through individual company sustainability commitments.

Future of Sustainable Finance and Market Reform

Regulatory Framework Evolution

The Brazilian green bond scandals are likely to accelerate the development of mandatory sustainability disclosure and verification requirements across major financial markets. The European Union’s Green Bond Standard, which requires independent verification and detailed reporting, represents the type of regulatory framework that could prevent future greenwashing scandals. Similar mandatory standards may be adopted in other major markets as regulators respond to growing evidence of systematic sustainable finance fraud.

Enhanced liability frameworks may emerge that hold financial intermediaries accountable for the environmental integrity of the instruments they create and market. Current legal structures often limit liability to issuing companies, enabling banks and other intermediaries to profit from fraudulent green bonds without facing legal consequences. Future regulatory frameworks may establish joint and several liability for all parties involved in sustainable finance transactions.

International coordination of sustainable finance regulation may accelerate as the global nature of environmental crimes becomes more apparent. The Brazilian scandals involve companies and financial institutions from multiple countries, requiring coordinated regulatory responses to be effective. Multilateral frameworks for green bond verification and enforcement may emerge from current bilateral and regional initiatives.

Market Structure and Technology Solutions

Blockchain and other distributed ledger technologies may be deployed to create transparent, immutable records of environmental performance and supply chain data. Current green bond verification relies on self-reported data and periodic audits that create opportunities for fraud and manipulation. Technological solutions could provide real-time, independently verified environmental data that makes greenwashing significantly more difficult.

Satellite monitoring and artificial intelligence applications may be integrated into green bond verification processes to provide independent confirmation of environmental claims. The Brazilian scandals were ultimately exposed through satellite imagery and ground-truth investigations rather than corporate reporting or financial audits. Systematic integration of remote sensing data into green bond verification could prevent many types of environmental fraud.

Standardized environmental accounting and reporting frameworks may emerge from regulatory responses to the Brazilian scandals. Current sustainability reporting allows significant discretion in emission calculations, supply chain monitoring, and environmental impact assessment. Mandatory, standardized approaches could eliminate many of the accounting manipulations that enabled the Brazilian green bond fraud.

Conclusion: Systemic Reform Imperative for Sustainable Finance Integrity

The interconnected web of Brazilian green bond scandals—encompassing over $5 billion in fraudulent or problematic sustainable financing—represents far more than isolated corporate malfeasance. These scandals expose fundamental weaknesses in the global sustainable finance architecture that have enabled systematic environmental destruction while channeling capital away from genuine sustainability solutions. The sophistication of the fraud, involving major corporations, international banks, and complex financial instruments, demonstrates that current market-based approaches to environmental protection are inadequate to address the scale and urgency of global environmental challenges.

The regulatory response to these scandals will likely determine the future credibility and effectiveness of sustainable finance as a tool for addressing climate change and environmental degradation. The SEC’s investigation of JBS, criminal complaints against European banks, and enhanced regulatory enforcement represent the beginning of a fundamental reassessment of how sustainable finance markets operate and are overseen. The outcome of these regulatory actions will establish precedents that could either restore market integrity or confirm that sustainable finance has become primarily a marketing exercise rather than a genuine environmental solution.

For institutional investors, the Brazilian green bond scandals highlight the critical importance of independent due diligence and the limitations of relying on corporate sustainability claims or third-party ESG ratings. The systematic failures of major banks, rating agencies, and sustainability consultants to identify obvious environmental fraud suggests that investors must develop their own capabilities for verifying environmental claims and assessing sustainability risks. The potential for significant financial losses and legal liability from fraudulent green bonds may force fundamental changes in institutional investment approaches to sustainable finance.

The long-term implications extend beyond financial markets to encompass the credibility of market-based approaches to environmental protection. If sustainable finance markets cannot prevent systematic fraud and environmental destruction, alternative approaches including regulatory mandates, public investment, and international cooperation may become necessary to address global environmental challenges. The Brazilian green bond scandals thus represent a critical test of whether capitalism can be reformed to address environmental crises or whether more fundamental systemic changes are required.

The path forward requires not only regulatory reform and enhanced oversight but also a fundamental reassessment of the incentive structures that have enabled environmental destruction to be profitable while penalizing genuine sustainability efforts. The Brazilian scandals demonstrate that without addressing these underlying economic incentives, regulatory and market-based solutions will continue to be circumvented by sophisticated financial engineering and corporate fraud. The ultimate success of sustainable finance will depend on creating systems that make environmental protection more profitable than environmental destruction—a transformation that requires far more than better disclosure and verification requirements.

Seeking clarity in the complex sustainable finance landscape? Our specialized advisory services help institutional investors and regulators navigate the evolving challenges of ESG fraud detection and sustainable finance due diligence. From supply chain verification to regulatory compliance strategies, we provide comprehensive support for organizations working to distinguish genuine sustainability from sophisticated greenwashing. Contact us today to explore how emerging regulatory frameworks and market reforms create both risks and opportunities in the sustainable finance sector.

Leave a Reply